Category Archives: uggghhh…technique

Tours De Farce

Modern was rather great today. I figured out how to do it without annoying my foot. I’ve discovered that the only thing that makes it hurt is putting even a little pressure directly on the outside of the joint, which happens with alarming frequency in modern dance. I simply faked my way through anything that involved that (safety releases, etc) and things went fine.

I’m still fairly terrible at remembering modern combinations, but that’s nothing new. It is slowly improving.

BW’s class tonight, meanwhile, was quite good once my body decided to wake up and participate. I think it was feeling sluggish because I’d just subjected it to a rehearsal followed by no stretching and a 20-minute drive. I suppose it was within its rights to feel grumpy about that.

Anyway, we did all the jumps today: so much petit allegro, followed by one grand allegro exercise.

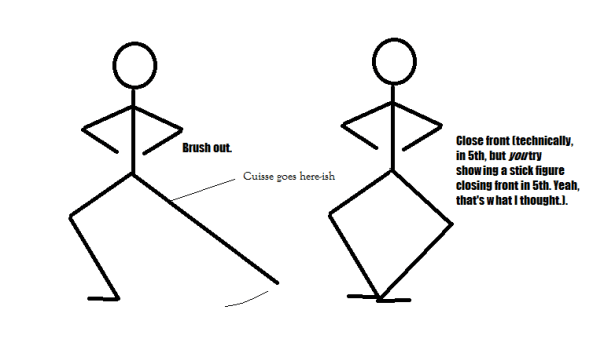

One of the petit allegro exercises involved temps de cuisse, which I’ve been erroneously calling temps de puisse ever since I for some reason decided it was, in fact, power-step and not thigh-step. But I was right the first time, which is funny for the very specific reason that I initially thought it was really neat that the step was named after a piece of armor, then disappointed that it wasn’t … but I was wrong, and it really is named after the piece of armor!

…Which is pretty cool, though POWER STEP!!!!!111oneoneone1one1onewon is also a pretty cool name for anything in ballet.

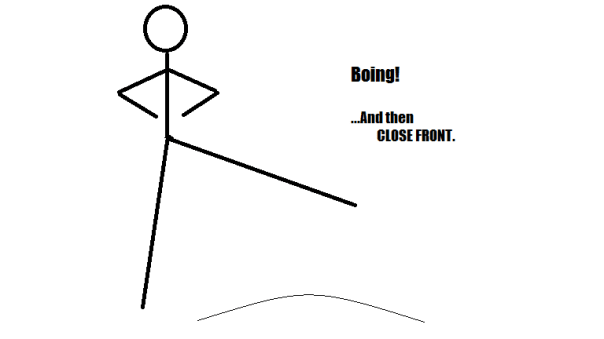

Anyway, turns out temps de cuisse is supposed to be done upstage to effacé. Also turns out that when you do it that way rather than trying to do it en face, it’s a hell of a lot easier.

Oh, and remember that you “BOING!” upstage to efface, which I completely failed to indicate here because laziness.

The weirdest bit is that I remember looking this up, but maybe that happened in a very vivid dream, and I can file it away with BW’s choreographic advice about rotting fruit?

This is the most important thing I’ve ever learned about ballet, and in fact about dance in general: with few exceptions, things are largely easier when you do them correctly.

In fact, I would almost go so far as to say that this is pretty legit advice for life in general.

I don’t actually remember the rest of that combination at the moment, though I know involved entrechats, because I had done fugly entrechats in the second petit allegro exercise and was startled that they miraculously just plain worked in this one (probably because I was busy thinking about temps de cuisse instead).

Anyway, for grand allegro, BW gave me the choice of various species of jetés across the floor or tours. I said, “Tours, because I never get to do them in any other class,” which met with approval 🙂

Anyway, BW gave me a little combination that went something like:

tombé

pas de bou-chasséi(1)

plié fifth(2)

tour

- This is that kind of hybrid step in which you begin to pas de bourré, but instead of simply going back-side-front to fifth, you go back-side-front straight to fourth through a kind of flying chassé.

- In this case, you’re practically doing a petit assemblé that lands fifth. It spring-loads the legs. Oy vey, does it ever.

I tried this a couple of times and alarmed myself by doing 1.5 tours instead of proper singles … and then I ran the combination again, got off a nice single, and promptly fell the feck over. Like three times.

BW said he’d had the same experience, and once in fact left class in tears because he couldn’t stop falling over. He also pointed out that falling over means you’re trying really freaking hard. Which, in fact, was true.

I’ve had a bad habit of doing itty-bitty little cautious tours, which probably have their place somewhere in the great universe of ballet, but honestly aren’t very interesting. I’ve decided that I’m going to launch all my jumps into space all the time (okay, okay, exept when we’re doing petit allegro), in the interest of actually A) being an interesting dancer and B) making the best possible use these giant slabs of ham with which the Universe has for some reason seem fit to favor me instead of normal human legs.

Anyway, after falling over backwards a few times, I decided to switch sides, and except for the part where my brain insisted the first time on doing the right-side variation anyway, the left side came off without any falling over. I then tried the right again, almost fell over but caught myself, and realized that a part of the problem was simply that I was instinctively trying to avoid putting my right foot down.

You can do tours to a single foot if you’re doing actually doing tour-to-the-knee, but you have to do it on purpose(1). Otherwise, you half-ass things and fall right the heck over.

- Even then, you do it by bringing the front leg to passé after lift-off, which neatly shoots it out the back because Physics, and then you land in an awesome-looking lungy-kneely thing so you can look all romantic and impressive and princely.

So now I know two different ways to fall over doing tours.

A. Forget to change your feet.

The first thing you do in a tour (well, after lift-off) is change your feet. If I remember correctly, not everyone does it this way, but it’s the standard, and the guys who change the feet last are stylistic mavericks. Anyway, I once tried doing a tour without changing my feet just to see what would happen. I managed to stay upright, but just barely; if I’d put any real force into it, I would’ve been flat on my tuchas in a heartbeat.

B. Change your feet, but then fail to actually put the one that started in front down all the way.

In a tour, your feet act as a kind of braking system. You load up a metric shed-ton of momentum, and changing your feet and sticking both of them on the ground allows you to oppose that momentum in a meaningful way so you don’t fall on your butt and roll, which seems like it might actually be a valid way to end a tour if you’re dancing a role in which that’s how you die, but probably should otherwise be avoided.

Artist’s depiction of how not to land tours. Any resemblance to Kokopelli experiencing wind turbulence is entirely coincidental.

Anyway, the falling-over-backwards bit was pretty hilarious, mainly because it was a complete surprise Every. Single. Time … at least until I figured out why I was doing it.

By then, it was just after 8 PM anyway, and we’d been working for more than 90 minutes, so we called it a night.

Sadly, I won’t have class with BW next week because of rehearsal, but he is coming to see us dance that Saturday.

This Saturday is our final fitting, and I finally get to find out what I’m wearing in the performance other than white socks and white shoes (SPOILER ALERT: YES, there is a shirt).

Tomorrow, we have Awesome Acro Workshops, followed by a weekend of madness and final costume fittings and a rehearsal on Monday.

Next week, I am taking Tuesday OFFFFFF.

On Technique: Frappe, Elevated

Fifth in a series of posts on the details of technique that focuses primarily on steps and aspects of dance that I’m struggling with. Take it with a grain of salt.

I find it helpful to write things out in an effort to get a grip on them. These aren’t so much instructions (though if they work for you, awesome!) as observations.

Today, in HD’s advanced class, we were given the option to do the frappé at the barre on flat or rélevé as we saw fit.

Since I’m trying to see my way back to being fit, I chose to do the whole combination on rélevé.

Frappré en rélevé has been a bit of a white whale for me for a while. I tend to knock myself off my leg. Today, HD fixed that for me.

The source of the problem it seems, is that en rélevé, I tend to snap! my leg out from the knee.

Not only is this bad for your knees, but it has a way of making your turnout muscles say, “Aw, hell naw!” and let go. Hence, the knocking-one’s-self-off-of-one’s-leg part.

HD caught this and told me to squeeze the working leg out, as if against the resistance of a Theraband (or, in my mind, a giant vat of chocolate pudding … I went to class without breakfast this morning).

On the second side, I tried it, et voilà!

Much better frappés en rélevé.

So that’s today’s snack-size serving of technical notes: yes, frappé should be quick and sharp, but it’s still a squeeze and not a snap!

That’s it for today. Problems to solve in the world, etc. (Dancer problems, but still…)

Technique: Hypermobility, Proprioception, and Balances

Third in a series of posts on the details of technique that focuses primarily on steps and aspects of dance that I’m struggling with. Take it with a grain of salt.

I find it helpful to write things out in an effort to get a grip on them. These aren’t so much instructions (though if they work for you, awesome!) as observations.

I’ve written a bit before about the often-ridiculous relationship between hypermobility, proprioception, and one’s extremities. In this post, I’ll take a closer look at that relationship—and especially on how it pertains to balances (rather than to balancés).

Remember this shot by Mas? At this angle of articulation, my wrist doesn’t even really feel bent.

To sum things up, proprioception(1) is the vastly under-celebrated sixth sense that tells us, among other things, where in space our body parts are relative to one-another. It depends in part on stretch receptors that hang out in the muscles and joint capsules.

- Wikipedia actually has a pretty good article explaining what proprioception does, why it’s important, and how it works.

Hypermobility, meanwhile, is a catch-all term for conditions in which one’s connective tissues are more elastic than average. In dance, this is both a blessing (see: Woot! Extensions!) and a curse (see: OMG WHERE EVEN IS MY BODY RIGHT NOW?!).

This, of course, makes perfect sense if you think about it. Dance demands both a huge range of motion and highly-developed proprioceptive faculties. Hypermobility enhances range of motion(2), but it reduces proprioception(3).

Moar behind the cut, because this is really long!

Technique: Don’t Fling The Baby

The second in a series of posts on the details of technique that focuses primarily on steps I’m struggling with. Take it with a grain of salt.

I find it helpful to write things out in an effort to get a grip on them. These aren’t so much instructions (though if they work for you, awesome!) as observations.

Hi. My name is Asher, and I’m a baby-flinger.

Wait, wait, wait! I don’t mean it like that.

I have never literally flung a baby. Hell, I’ve (still) never even held a baby. Those things are terrifying. I reserve my child-handling efforts for those at least one year of age, and by then, they’re toddlers already.

What I mean is that I do crazy stuff with my arms when I’m doing turns. Sometimes, anyway.

And this isn’t your standard crazy stuff, like the traditional “winding up for the fast-ball pitch” method or the beginners’ special “just not even having any idea what to do with the arms in the first place” method. I’ve (mostly) overcome the fast-ball method and I don’t think I ever suffered from the “not having any idea” method(1).

- At least not with turns; with everything else, on the other hand…

No, this is something else. Something, erm, special.

So here’s the thing:

When you do turns, your supporting-side arm opens in preparation, then closes as you initiate the turn.

Your shoulders and hips stay together.

Your working-side arm does not then lead the supporting-side arm in a breakaway that basically resembles attempting to rock-a-bye baby right into space.

Me? I’m a baby-flinger.

Apparently, just as I get excited about piqué turns and sometimes wind up doing them as if they were some kind of insane piqué-jeté en tournant, I get excited about pirouettes and try to launch babies into orbit.

Clearly, they don’t need my help(2).

- Vintage Chinese Space Program poster, via Ricardo Goulart, via Tumblr, via shameless internet thievery. You’re welcome.

My supporting-side arm closes to meet the working-side arm, and then they both continue merrily along on a trajectory that throws the whole thing off kilter(3).

- The fact that I have ever managed a triple turn is particularly astounding in light of this revelation.

Obviously, this is a problem—and it’s one I never noticed before JP subbed for advanced class (because Nutcracker) and called me out on it.

Oddly enough, when I control it, turns are so much easier.

Now, if I was a Real Grown-Up™, I might just remember that my arms should stay with my body and not go sailing off on their own mission.

But I’m not. So instead, when it’s time for turns, I tell myself:

Don’t fling the baby!

It’s probably worth noting that I do a lot more of this when I’m turning from fourth or second. Why? Because those are POWER TURNS!!!!!!!!1111oneoneone1one

And apparently I am maddened by power. But with great power comes great responsibility—specifically, the more powerful the turn, the more responsible you are for NOT FLINGING THE BABY, for goodness’ sake.

If you’re having trouble with turns and you’ve already checked and found that you’re:

- not winding up for a fast-ball pitch

- not letting your shoulders twist away from your hips, and

- not just completely uncertain how to do turns in the first place,

consider asking yourself, “Am I flinging the baby?”

Parents everywhere will thank you.

Or maybe they won’t, as previously noted:babies—those things are terrifying(4).

- Though this doesn’t mean I don’t want one of my very own sometimes. I have noticed that they’ve grown less terrifying in recent years, culminating in the birth of O, the Actually-Adorable Poster Baby, to one of the Aerials Goddesses who owns my studio.

I forgot to note that, on Saturday, I finally got the thing where you tour lent/promenade just by scooting the heel.

Seriously, I thought I had this, but evidently I didn’t. When you’re doing it right, you really don’t have to bounce up onto semi-demi point.

On the other hand, you do have to engage the living daylights out of your turnouts and keep everything square.

Obviously, this is a topic for another post, but I thought I’d write myself (and you) a note about it so I don’t forget.

Technique: Notes On Tombe-Coupe-Jete

I’m launching a series of post on the details of technique. It’ll probably consist primarily of steps I’m struggling with, so take it with a grain of salt.

I find it helpful to write things out in an effort to get a grip on them. These aren’t so much instructions (though if they work for you, awesome!) as observations.

Tombé-coupé-jeté is a subset of coupé-jeté en tournant (if you do jazz, you might know this as a “calypso,” if I understood my classmate correctly).

As its name implies, it’s a compound step. The elements are:

- a tombé into a

- turn at coupé

- that lends its rotation to a jeté

Some form or another of coupé-jeté en tournant shows up in men’s technique a lot—QV Le Corsaire’s famous (and famously-hard) Slave variation, the Pas de Trois from Swan Lake, a whole bunch of stuff in Nutcracker, etc, etc.

Coupé-jeté pass starts at ~1:20 This guy knows what he’s about.

Also, I like the way he moves.

The tombé version is the one I’m concerned with here.

I’ve been wrestling with making my tombé-coupé-jeté consistent on both sides so I can use it in choreography without having to think about it (because thinking is basically death to my ballet technique; it makes my brain overheat and crash).

The basic mechanics, traveling right, go like this:

- Tombé onto the right leg.

- Bring the left leg to coupé while executing a turn en dedans.

- Your arms help to provide momentum for the turn.

- Don’t leave your body behind!

- Transfer weight onto the left foot. Your left leg will be in a demi-plié.

- Simultaneously, grand battement the right leg just as you would for a plain old vanilla jeté.

- Spring off the left leg.

JP’s notes:

- For men’s technique: tombé to second (you get a bigger jump, and men’s technique is basically be distilled into How To Get A Bigger Jump).

- I realized today that I kept tombé-ing to something like 2.5ième. Bleh.

- It works a lot better if you actually really do tombé to an actual 2nd.

- The turn happens in the coupé.

- NOT in the tombé.

- NOT in the jeté*.

- *The remaining momentum from the turn will cause the jeté to rotate slightly, but if you think of the turn as being in the jeté, you’ll inevitably add a rond-de-jambe, and everything will go right to Hell in a hand-basket.

So, basically, this is “how not to pirouette,” but, eh. You get the point.

- I tend to start unfurling my working leg at the wrong point in this turn. DO NOT DO THIS. It throws everything else off, and also results in a wobbly flight path.

- The right leg sweeps STRAIGHT OUT, as in grand battement, avant or to 2nd (I’m not actually sure if one is correct and the other incorrect; I didn’t think to ask JP).

- The working leg does not rond.

- I repeat, the working leg DOES NOT ROND.

- I find that it helps to think “Grand battement!” rather than “Don’t rond!”

So let’s think about how this all works on the right.

- The tombé loads the right leg, providing impetus for the turn just as the plié does at the beginning of a pirouette.

- The arms come together to add to the momentum of the turn as the left leg snaps to coupé.

- The body has to stay connected—the shoulders and hips must travel together—in order to execute this movement well. This is true for all turns, but especially true for coupé-jeté en tournant.

- The coupé builds momentum that will allow the jeté to sail along a curvilinear pathway.

- At the end of the turn, the weight is transferred to the left leg in demi-plié. The right leg sweeps straight out to initiate the jeté.

- The jump lands on the right leg. It’s possible to move right into another coupé-jeté en tournant or into another step entirely.

Here’s what I tend to do wrong when doing tombé-coupé-jeté en tournant.

- I tombé into some weird 2.5iéme kind of position instead of a clean 2nd.

- I fail to keep my hips and shoulders together.

- I try to come out of the turn at coupé to soon.

- I sometimes snap the leg up as one would in saut de chat instead of sweeping it straight up.

- I rond the leading leg in the jump to compensate for exiting the turn too early.

In case you’re wondering, yes, I did do about a million slow-motion coupé-jetés on my living room carpet while trying to work all of this out.

Anyway, now I know what I’m doing wrong, so I should have a better time getting it all sorted.

In the meantime, here’s a really good video that demonstrates coupé-jeté en tournant. I should probably note that I’ve only watched it with the sound off, so I have no idea what it sounds like 😛

Balances

Tried Aerial A’s exercise with my worst balance, coupé (avant), today.

Holy Entrechats, Bournonville-man! It works!

The exercise in question(1), by the way, is a painfully slow piqué into whatever balance.

So, with Turnout Mode Engaged:

- point (with all your heart, all your mind, and all your soul) through the entire leg that’s going to be the supporting leg

- keep the hip socket engaged

- soft demi-plié the other leg

- keep the hip socket engaged

- push (don’t spring!) onto the demi-point of the supporting leg

- KEEP THE HIP SOCKET ENGAGED(2)!!!

- slowly lift-rotate the working leg into place

This gives you time to think about what your back, hips, etc are doing.

I’ve realized the my back is totally my nemesis in coupé—in retiré, I automatically engage the bejeezus out of my core (because that is part of the recipe for a high retiré), but in coupé I don’t, and then my tendency to throw my shoulders and head back just screws the whole thing right up.

The various arabesques and attitude arrière are easier because they’re counter-balances, which means you can fake ’em’ til you make ’em, to an extent.

Meanwhile, attitude avant and simple balance à la seconde are hard enough that I have to think about them (and both require intense core engagement). Likewise, balances in extension (usually via développé) in the various directions engage the core automagically for me.

Hence, coupé balance is hard because it’s easy.

Ah, yes. That’s right. This is ballet, the art of counter-intuition, isn’t it?

- I’ll see if I can get Aerial A to collaborate on a video for this!

- If you’re like me and you like to show off your flexibility and hyperextensions and beautiful lines and you have intermittent issues with your supporting leg feeling squidgy at the top, you might be failing to extend from the hip socket, and instead making your whole pelvis go all cattywampus and sideways ‘n’ shizzle. See below.