Category Archives: #dancerlife

Oh, BTW, I Got Interviewed!

I’m pretty sure that in my surprisingly-intense anxiety about trying to teach a partnering class via Zoom, I forgot to mention that Ambo Dance Theater‘s* Linsey Rae Gessner recently interviewed me for her new podcast series, Be The Flow, in which she and her guests reflect on “…the importance of ART and the role it plays on the community with the intention of unifying creativity through compassion and knowledge.”**

*yes, that is me front and center on Ambo’s header ^-^ It’s a still from “only weeds will rise in winter,” one of the first pieces I performed in, which examined the ways that poverty influences the lives of the people who experience it.

**from Be The Flow’s landing page

Amazingly, I sound like WAY less of an idiot than I would’ve expected, although my headset mic is adjusted … less than perfectly, shall we say, so I also sound a little fuzzy.

But still! As someone who listens to podcasts a lot, it’s interesting to hear yourself on an actual podcast and to realize that, hey, you actually sound like a fairly competent person, LOL. (IF ONLY THEY KNEW, amirite? Hahaha…)

Anyway, here’s an embedded player if that sounds like it might float your boat:

And here’s a direct link in case you should feel inclined to check it out that way ^-^ You can also check out Linsey’s other interviews and follow her podcast on Spotify from there.

For some reason I didn’t include a link to this blog in my bio, so while I might not sound like an idiot, clearly I sometimes still am one ^-^’

DancerLife: Food (Part 1)

Upfront disclaimer/disclosure thing: I am definitely not a nutritionist, as you’ll probably realize if you read the rest of this post, which is mostly about stupid food-related mistakes I made last season. This post is not intended to diagnose or treat any medical condition, nor should it be taken as advice, unless the advice is: If you have questions about feeding yourself as a dancer, maybe go ask someone who really knows their stuff.

I’ve written about food before. Probably a lot. I like food, though I struggle with food sometimes. I also generally quite like eating[1].

- Except, apparently, when I don’t. I’ve recently experienced a baffling lack of interest in food itself: I’ve been in this place in which I would be perfectly content to live on peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, or really whatever requires the least thought or effort, day in and day out.

On the whole, I’ve felt like I’ve had a pretty good grasp of basic nutritional science (hard to get through a Bachelor’s of Science degree that includes Anatomy & Physiology without understanding at least a bit).

I’m sufficiently equipped that I mostly manage to steer clear of trends based on junk science or poor data and to regard with equanimity the ones that might, in terms of their originators’ ideas about science, be based on shaky logic, but which still work well for people in practice because they’re motivating in whatever way and manage to get the various nutrients in.

What I haven’t had, as I discovered over the 2019-2020 ballet season, was the slightest shade of an idea as to how to actually feed myself for performance while dancing 30 hours per week, teaching about six hours per week, and driving an extra 80-90 minutes per day 2-3 days per week between those two gigs.

This was especially difficult on days when I left my teaching job at 8:30 PM and didn’t arrive home until after 9, chronically underfed (though I usually didn’t realize that) and with little time to eat, shower, prepare food for the next day, and wind down before I had to be asleep.

To a great extent, this was my own darned fault.

I extrapolated as follows:

- P1: I have a fairly sound working knowledge of basic nutritional science.

- P2: An awful lot of the nutritional advice I know how to find runs contrary to basic nutritional science.

- P3: I am broke and can’t afford to go see a nutritionist.

- Therefore, I should just stick with what I’m doing.

Or, well, something like that.

Yes, y’all, I am an idiot. Sometimes, anyway. Even often.

I think I also wasn’t sure who to ask: like, let’s be frank. Dancers are mostly paid what is known, in the technical language of economics, as “bupkis.” Or possibly “peanuts.” (In fact, since I have volunteered at events where one of the perks was free access to peanut-based trail mix, I can literally say that I’ve worked for peanuts. Hmmmm.)

Regardless, dancers be broke, and qualified nutritionists who have adequate knowledge of the nutritional requirements of full-time ballet dancers be … not cheap. (Nor should they be. They train for years to master their specialty, just like we do.)

So you had better believe that when I learned that LouBallet’s MindBodyBalance program was hosting a Zoom-based nutrition workshop with an actual qualified person who actually understood things about how to feed dancers, I jumped right on that enroll button.

Anyway, today, Becky Lindberg Schroeder of Lindberg Elite Nutrition (she’s also on Insta!) gave us a really solid talk, with time for discussion, about how to feed ourselves for performance as dancers.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I realized I’d been going about things … well, not all wrong, but wrong enough.

The two most important things I’ve been doing were basically:

- Not eating enough

and - Not eating often enough.

Somehow, I felt like I shouldn’t be eating during the 5-minute break between class and the beginning of rehearsal. I would usually surreptitiously scarf an apple, but I felt like I shouldn’t.

Why?

Honestly, I think I just noticed that few of my fellow dancers shoved a snack into their faces during that interval. Outside the studio, I’m fairly resistant to peer pressure, but life inside the ballet studio is different, especially as an apprentice who doesn’t feel super confident about his place in the company.

Now that I’m writing that “out loud,” of course, it seems kind of dumb.

You can’t stuff yourself with a huge breakfast before class if you want to get through class without, at best, being miserable or, at worst, puking … but if you eat a lighter breakfast at 8:30, by the time class is over at 11:30, it seems entirely reasonable to assume that you’re going need to top up your fuel tank.

If you try to hold out until lunch break at 1, you’re likely to be hangry before you get there. (Regarding which: yes. On days that I’ve failed to eat any kind of snack at all, I’ve usually been deeply hangry before lunch break rolled around.)

Becky’s suggestion that we eat every 3-4 hours made that all make sense. In fact, it makes so much sense that I’m now wondering how I failed to grasp it before. Then again, that’s why she’s a high-performance nutritionist, and I’m not.

Perhaps even more importantly, I don’t think I really understood the effects of chronically low blood sugar on both performance and body composition.

Becky showed us a diagram illustrating the point that the range in which the human body works best falls between 80 and 100. My fasting blood sugar is rarely higher than 70 (I forget what the units in question are right now, sorry). I’m impressed if it’s 72; the one time in my life it was as high as (GASP!) 74, I wondered if I’d randomly awakened and eaten something in the middle of the night and forgotten about it.

Anyway, <70 is low. The typical response that garners during a medical exam is basically, “Cool, no need to worry about diabetes!”

But it turns out that when your blood sugar level is low, your body really does burn muscle and hold onto fat. I kind of knew that: we’ve all heard of “starvation mode.” What I didn’t know was that your body doesn’t wait around for a couple of weeks before heading down that road.

So, in short, I probably wasn’t doing myself any favors by avoiding carbs in the morning.

This certainly explains why I’ve felt better on the rare morning that I impulsively threw a donut into the mix because I happened to stop for gas, or had to use ACTUAL SUGAR in my coffee because I ran out of stevia, or whatever.

If you’re starting with basically an empty tank, putting anything in it is going to help. It’s not like you’re body’s going to ignore fuel simply because it’s not Eleventy Octane Super Premium Ultra Plus, Now With Scrubbing Bubbles.

Your body, at that point, just wants ANYTHING. And if you don’t give it something, it’s going to assume that it should hold on to its emergency stores and tap the muscles instead.

That might also explain why basically surrendering to chronic disorganization, purchasing an immersion blender, and just making huge smoothies with some protein stuff (usually pasteurized eggs) and a handful of trail mix (peanuts and almonds … protein and fat in one happy little package) for breakfast and packing more of said trail mix to eat with lunch correlated with an unexpected drop in my body fat percentage.

Obviously, without a controlled experiment, causality is danged hard to determine–but in retrospect, it seems like maybe one way of accidentally starving myself was worse than the other. The one that gave me some carbs, protein, and fat, while still not ideal, was probably less bad.

I also made the mistake of thinking that my other frequent snack choice–inexpensive protein bars, because broke–was somehow … not good enough. Again, that seems silly now. The protein bars in question may be fairly processed (though they’re still mostly made of things that are recognizeable as food, albeit in small chunks), but they do the job of being quick and easy to eat when “quick and easy” are probably the most important criteria. You might have the best apple in the world, but if that’s all you’ve got, and you can’t finish it in 5 minutes, it’s not going to do the job.

Anyway, the most important takeaway for me was that I need to eat more, and to eat more often, than I did last season. Well, that, and to not eschew nutrition in bar form, because that’s often going to be my best bet.

My breakfasts, snacks, and lunches were uniformly underpowered last year (I’m not going to say “too small”), while my dinners were … spotty. I didn’t have time for a full meal between rehearsal and teaching, so by the time my classes let out, I was both incredibly hangry and in no position to drive for 40-50 minutes without eating.

Since I would, inevitably, have also run through the woefully-inadequate supply of food I had packed for the day, I typically resorted to drive-through dining, but usually (in an effort to reduce the artery-clogging effects of fast food) I’d get the smallest meal I could find.

Then I’d be mad at myself when I was starving at 10 PM, or wonder why I was so hungry at 1 AM that I woke up and couldn’t get back to sleep without eating something.

You guys. In retrospect, I’m really trying to figure out … like … how I didn’t figure it out -.-

Part of the problem was my tool set. Basically, I was whacking away with a hammer, mentally screaming, “Why is it so hard to saw through this log???!!!!” I kept focusing on how to eat better at dinner time, when I would’ve done better to just eat a little more and a little better across the whole day.

Anyway, one of Becky’s smart, actionable suggestions was to literally write out your daily schedule (not too obsessively: sometimes lunch break is at 12:53; sometimes we get really into rehearsal and at 1:30 Mr D looks up and goes “OMG, sorry, you guys! I haven’t given you a lunch break!”) and figure out how to feed yourself around it.

Which … oh, my G-d. That’s brilliant.

Becky’s presentation also introduced Team USA’s Athlete Plates[2]–three useful visual guides to adjusting nutrition for the demands of your day. They’re less about telling you specifically what to eat than suggesting how to proportion your meals to keep yourself well-fueled. This is exactly the kind of information delivery I’ve been yearning for: visual, so you can use it at a glance, but with lots of deeper information readily available.

- You can find PDF guides to the Athlete Plates, along with lots of other great information about nutrition for athletes, on Team USA’s Nutrition page.

In short, I came away from this workshop with a much better sense of how I, a broke-ass dancer with ADHD and time-management challenges, can make a plan to keep myself well-fueled that actually fits into my life.

So that’ll be Part 2 of this post … because right now it’s dinner time, and I’m hungry.

DancerLife: A Series

Okay, while the world is (justifiably) exploding, it turns out that I do need to prepare myself to go back to work in the fall: my contract has arrived, and with it the knowledge that all my efforts to plan and implement plans between now and then are likely to go awry, but that it’s still worth attempting to plan and to apply lessons from last season to making next season better.

Since writing this blog is part of how I think about things (indeed, that’s more or less its primary purpose), here we are.

Anyway.

I’m sure I’ve mentioned that, for many of us, ballet isn’t so much a hobby or a job as an all-encompassing avocation that basically asks everything of us.

As a dancer, you reach a point at which either you’re like, “Nah, I’m good,” and just go on doing a recreational class once or twice a week, or you’re like, “I AM CALLED” and you basically hand Ballet (or Modern, or Hip Hop … whatever your idiom is) the keys to your life and it moves in.

That might happen when you’re six or when you’re sixty, and other things might try to get in the way, but when you’re called, you’re called.

(Quick note: whether dance is recreation or vocation, you get what you need out of it. No shade from me for recreational dancers. For that matter, honestly, they’re probably the saner demographic anyway.)

In everyday English, we mostly use the word “vocation” to mean, basically, “job.” For many, it’s that thing you do so you can do all the other things you’d do anyway (and that’s fine, too, though our work culture tends to make it feel unfulfilling -.-,).

In other contexts, the word “vocation” means “a calling:” the thing you do because your soul, or whatever, is irresistably drawn to it. It’s why people become monks and nuns and solitary ascetics that live in the desert. (And probably also physicists and mathematicians and academics in general.)

The lives to which such people are called can’t be neatly divided between “work” and “life.”[1] To be a monastic or, for that matter, any serious practitioner of Zen, is to live a life in which there is no division between religious/spiritual/philosophical and secular life (qv Jack Kornfield’s After The Ecstacy, The Laundry or Thich Nhat Hanh’s Peace Is Every Step).

- Hypothetically, this is equally true for everyone? But in terms of lived experience, these tend to be quite different animals.

Being a dancer is very much the same. Dance as a vocation demands wholesale devotion.[2] It sets up shop in your kitchen, your bedroom, your wardrobe. It decides when you can hang out with friends who don’t dance, when you can stay up late, when you need to spend three straight weeks lying in a hot bath because #Nutcracker has just ended.

- This is largely true for artists in general, come to think of it–but dance, because it is so physical, is really good at making its demands felt. It’s also one of the rare artforms for which solo practice is an exception, rather than a rule.

If so, you are mistaken.

Anyway, we toss about the hashtag #DancerLife all the time (and often in jest), and I think it’s a useful idea. DancerLife is all-encompassing.

And since there’s a learning curve involved in figuring out how to make it all work, I’m going to spend some time writing about how I’m learning to make it work for me.

I was also going to write only one post today–one about nutrition, preceded by a very brief introduction to the idea of DancerLife: The Series. But since it seems I’m constitutionally incapable of discussing an abstract concept in fewer than a jillion words … here we are.

So consider The Series introduced, and I’ll go write the first “official” post, which will be about nutrition and eating and not becoming ridonculously hangry in the middle of one’s workday and stuff like that.

Video: It’s Not Just For Insta Anymore

In ballet, as in life, there are things you know that you know, and things you know that you know but maybe kinda don’t really know[1].

- …And also things you know that you don’t know, and things that you don’t know that you don’t know, but … ugh, let’s just start with the stuff we supposedly know. I’m too tired for the, like, epistemology of epistemology right now.

Like, you know that what you do at the barre is important. Foundationally important. Literally everything in ballet, your teachers tell you, is founded on the work you do at the barre.

…And yet it can actually be kind of hard, sometimes, to really feel what that means.

If you’ve been dancing for more than, like, five minutes with good instruction, you’ve probably heard the maxim that everything in ballet is essentially an extension of plie and tendu (some add rond de jambe to the mix; others argue that rond de jambe can be included in the “extension of tendu” category … I think both arguments have merit, so That’s Another Post).

If you’ve been dancing for more than five years with good instruction, you’ve probably experienced that idea directly often enough that it has taken on gut-level meaning.

You have learned to feel that your grand battement is just a tendu at maximum amplitude; that a waltz turn is just a bunch of plies and tendus strung together; that even a double tour is basically a plie that stretches with a lot of oomph.

That does not, however, always translate directly to the complex movements you do once you leave the barre. Knowing with your brain is not the same thing as feeling with your body, etc.

And this is where video comes in.

I think I’ve written a couple of times about the thing that makes video such an exceptionally useful tool for me–specifically, my proprioception is weird because of Ehlers-Danlos, so I can’t always actually feel what my body is doing relative to itself. Video is the best tool I’ve found for figuring out the difference between what I feel like I’m doing and what I’m actually doing.

Sometimes, though, it’s also a goldmine for technique.

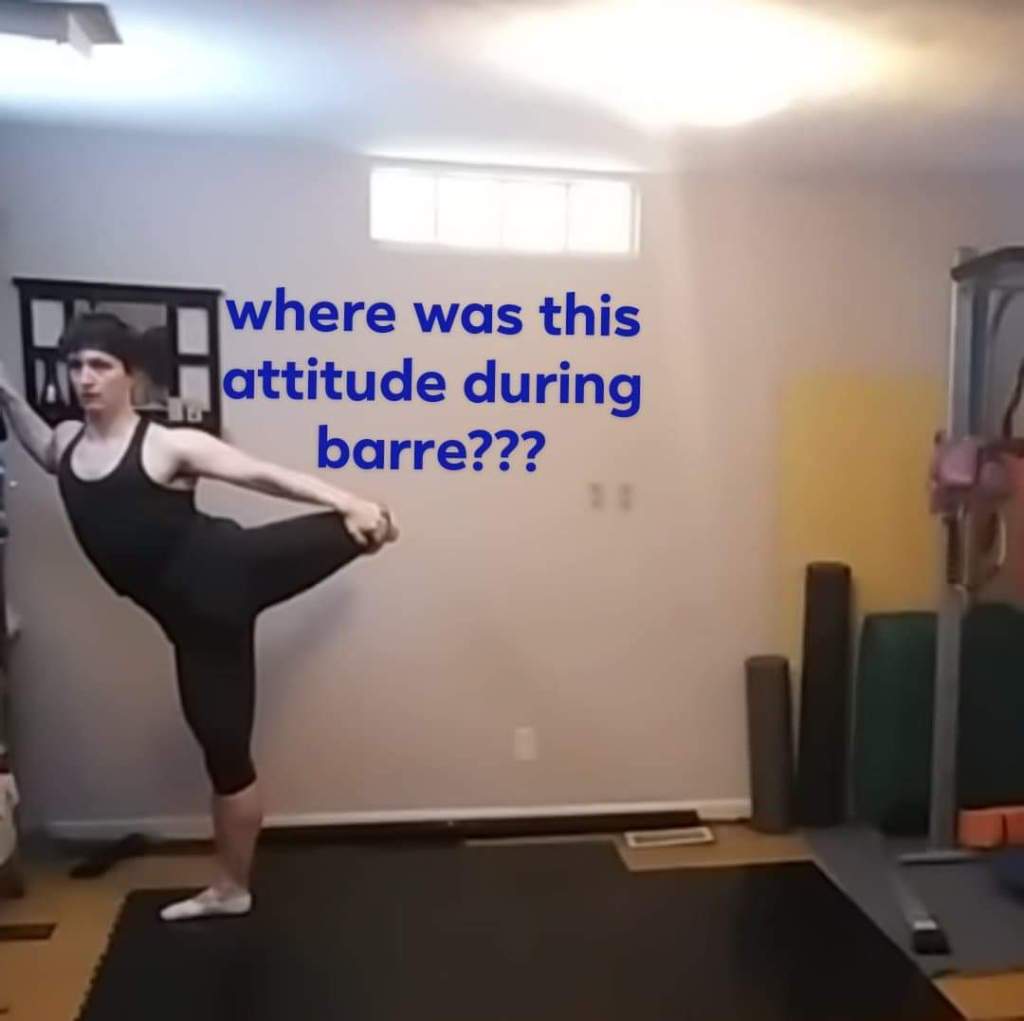

Case in point, this:

I’ve been trying to make my body sort out the relationship between the Bournonville grand jete and … to be honest, basically everything. I mean, like, yes: of course I realize that it’s a prime example of “it’s just tendu and plie, but with a little chutzpah,” but somehow I still feel like my execution always cuts a corner somewhere.

The reason that I feel that my execution of the Bournonville jete cuts a corner is that it does.

Literally.

I’ve been so busy thinking about Bournonville jete being a leap that I’ve been completely overlooking the fact that the leap will take care of itself if you DO THE REST OF THE TECHNIQUE CORRECTLY.

Functionally, this means that instead of brushing and pressing my leading leg and using the combination of that kinetic energy with the potential energy stored in the plie of the second leg, I’m sort of frantically flinging my first leg and throwing my body after it, taking off before the leading leg can do its job (which is to set the height of the leap and then STAY THERE–that’s where control comes in), and generally bungling the entire procedure.

I’m flexible, so I come closer to getting away with it than someone would who can’t just throw a leg wherever, but it’s still not good enough.

(Ballet: it’s always easier when you just do it right, and somehow that never ceases to be completely shocking.)

So, the picture above isn’t technically of a Bournonville jete. It’s technically a picture of … erm. Some kind of enormous cloche? I’d honestly have to go back and watch the video again; my brain is so cooked right now I don’t even remember which exercise it was (it was before grand battement and after degage *shrug*).

BUT.

When I watched this video, I instantly and powerfully understood that this picture is HOW YOU DO a Bournonville jete, or really any grand jete, and make it count[2].

- Okay, full disclosure: my upper body shouldn’t start this far back in an actual grand jete, unless I want it the leap to travel straight up I guess? But that’s actually one of the things I need to fix in my grand jete: I often leave my body behind, costing myself both travel and elevation.

What I do remember about this moment was that it was a cloche through from back to front, brushing strongly through first and pressing the leading leg up (as if against a weight: that was JZ’s main correction for me on Thursday–which, by the way, is exactly the main thing I’m focused on improving in my dancing as a whole).

On the first side, I’d relied (as I always do) too much on momentum and not enough engaged strength: I threw the leg (to be fair, jete literally means “throw”) in a way that meant I was no longer in control of it. My leg was on one journey, and my body was on another–their destination was the same, but for all intents and purposes, the leg was taking the early express train and the body was taking a slightly later local. That makes it kinda hard to keep the movements connected, you know?

JZ said to me, “Less momentum; more strength–like lifting a weight with the working leg.” I applied the correction on the second side, and this was the result.

Even though I’ve done an exercise specific to grand jete that uses this motor pattern–done it in a few different schools, in fact (my childhood studio, LouBallet, the Joffrey, LexBallet, pretty sure Naples Ballet)–I’ve somehow never connected the exercise that I was doing in JZ’s class on Thursday with grand jete.

And yet, there it is. If I sprang off that deeply-loaded right leg, I would … well, okay, in this case, I’d crash directly into the wire storage rack that’s like two centimeters from my left foot o.O’

BUT, if I did that in, say, a proper ballet studio … okay, and if I kept my back a bit more lifted … the result would be a lovely grand jete. The position I’m in doesn’t really need to change (except for the fact that my upper body needs to be a little closer to my free leg); I would just need to kind of … let go of the ground. Just add a little spring[3]. And then sustain the leading leg by pressing it up, as if under a weight[4].

- In case you’re not familiar with the distinction, the Bournonville grand jete is done with the back leg in attitude. Obviously, for the … other version, I’d need a little more spring, to get that back leg all the way straight.

- I love that analogy, because it summarises everything I love about the way Roberto Bolle moves: his movements are always at once contained and free; controlled and fluid. There’s always a sense almost that he moves against the resistance of a thicker atmosphere than the one most of us inhabit. The idea of pressing into a weight helps me think about how to achieve that feeling without becoming tense and unfree.

Somehow, the video that yielded this picture has helped me understand what I am and am not doing correctly when I do grand jete. (And, in fact, that I’m doing almost everything in grand jete incorrectly much of the time, although sometimes I get it right by accident and something beautiful happens.)

It might’ve taken me another five years to figure that out otherwise, because it’s incredibly difficult to see yourself doing a grand jete or any other large, complex movement (trying to watch yourself in the mirror screws up the body mechanics). I certainly get corrections on my technique all the time (that’s just life as a dancer), but video makes it easier to sort out what all those corrections aim to impart.

In short: if you haven’t tried shooting video of yourself in class, I highly recommend it.

Obviously, in a normal class, you should ask permission first and make sure your classmates are okay with it (my experience has been that they’re usually either like, “Sure as long as I never have to look at myself in it XD” or “OOH YES CAN I HAVE A COPY PLS????”).

Likewise, video alone won’t replace the guidance of a good teacher.

But for me, video has become a critical tool for analysing my own movement and figuring out how to improve it.

At least, once I got over the natural desire to bury my head in the sand and never watch myself dancing again ^-^’

Suddenly Summer o.O

Erm, so, apparently the FSB school year is over! And I missed the memo! (*sarcasm* OMG, can you believe it?! I, of all people, lost track of the calendar! THAT NEVER HAPPENS! */sarcasm*)

Like, seriously, a part of my lesson planning process for my 3-4 Year Olds class, I choose a class theme for each week, and I post the week’s theme with a related printable coloring page to FSB’s facebook page … and I popped it up there for this week and then an hour later our school admin called me up like, “Guess what! We’re on break!” XD

Anyway, I’m sort of vaguely staggered that I have now made it through an entire academic year of teaching.

Sometimes I feel like I’m really getting the hang of it, while other times I feel like I’m still just desperately treading water. Still, there’s nothing like an arbitrary temporal marker to awaken one to the fact that, somehow, one is actually Doing The Thing.

So I’ve now officially been a ballet teacher (OMGWTFBBQ) for a year and a ballet dancer (in a company) for two years.

Watching video of myself from this morning’s Zoom class[1], I can see that I’ve come a long way as a dancer in the past two years. This morning I was tired and groggy and … stiff might not be the right word, in that my body wasn’t stiff, but my movement quality was stiff AF? Like, I can see that my brain is kind of running in slow motion, ticking off individual steps and kind of grinding gears between them, so The. Phrasing. Is. A. Bit. Staccato.

- Video is a phenomenal self-teaching tool, and I keep meaning to write a post about it ^-^’

…And yet watching myself I can still see that this person here, for all his faults, kind of knows what he’s doing. Mostly.

Two years is as long as I’ve ever held any continuous job (or, well–just over two years, really)–but back then I didn’t see the job that I had as a career path. It was a thing I was doing to make money while I figured out what I actually wanted to do with my life ^-^’

Now I’m getting paid a lot less, but working to build a career, which isn’t a thing I ever envisioned doing until I came back to ballet, and even then it took quite a while before I felt like I had a snowball’s chance. Full disclosure: sometimes I still don’t feel like I’ve got a snowball’s chance. Like, part of me is like, “Okay, dude, keep your head down so The Powers That Be don’t notice that you’re Doing The Thing.”

Imposter syndrome still makes appearances, of course, and every time I refer to myself as a professional dancer, there’s a part of my brain that winces and goes, “SHUT UP YOU IDIOT DON’T JINX IT.” (That part of my brain apparently doesn’t do commas.)

Imposter syndrome notwithstanding, though, I feel like I’ve found a place in the world in which I actually fit.

Ultimately, I do rather think that’s the only way to become a dancer. It’s too hard otherwise. Either there’s something within you that drives you to dance, no matter how wildly impractical it seems, or there’s not (and that’s okay: like, I’m not driven to be a chef or an investigative journalist, but I love the work they do, and I’m so glad they do it).

I’m not saying that if you don’t dance professionally, you’re not a dancer. training, talent, and physical aptitude alone aren’t enough to make that happen–there’s a lot of chance involved; being in the right place at the right time, basically.

Like, I just happened to wander across Mr D’s radar at a time when he needed guys for The Sleeping Beauty, and then the person who was going to be Drosselmeyer had to back out, and since I was going to be there anyway, Mr D figured he’d just put me in all the things. Likewise, I happened to have met Dot at LexBallet’s SI (and again at PlayThink), and she mentioned to me that Gale Force Dance was holding an audition, which ultimately led both to dancing with GFD and teaching at FSB.

Not everyone stumbles upon circumstances like these. But if you can’t imagine living without dancing, if the studio is where you feel most at home, if you do everything in your power to find a way to dance as much as you can (even if that means you don’t get to dance very much), you have the heart and soul of a dancer.

Next year is still up in the air, a bit: we don’t know yet when, or even if, theater venues will reopen, or what that re-opening will look like. We have no way to know what the changes in question will do to ballet company budgets, or to arts funding (public and private) in general. I don’t think we even know what the rehearsal process will be.

For now, though, I’m just happy to have made it through a year of teaching.

I’ve concluded that adapting to a new job–especially one in a new field–is always a bit of a baptism by fire.

Whether or not you’ve completed formal coursework in teaching, it’s impossible to know before you begin what your students will be like, how they’ll respond to your personality, and so forth. You also don’t know how you’ll operate as a teacher.

Likewise, you learn to be in a ballet company by being in ballet company (this is one of the reasons that Youth Ensemble, Studio Company, and Second Company programs are so valuable).

Nobody can ever say for sure what the future will bring, but generally speaking accumulated experience makes it easier to do whatever thing you’re doing.

Anyway, that’s it for now. SI next week, then who knows what will happen.

Keep dancing, friends.

Unexpecto Coronum

Bit by itty-bitty bit, I seem to be resuming my life as a dancer.

Not, of course, in the sense of going out and dancing with other people in the studio. Rather, in the sense of finally taking class via Zoom (with a fantastic teacher, Johnny Zhong) on a regular basis … or, at least, I’ve hauled my butt to class twice this week.

Continuing to take class no longer seems like something that’s going to be a struggle against the tides of depression and exhaustion that have beseiged me for however many weeks.

Not that they’re, like, gone … but on Monday this week I hauled myself out of my Personal Doldrums and made myself take an actual class with an actual teacher who could actually see what I’m doing and correct things and (amazingly) tell me when I did something well. And then today I took his class again. And now taking class twice next week seems like given.

(Given the enormous lapse between my last real class and the first one this week, I wasn’t expecting to do anything well.)

Anyway, it took me a long time to get to this point.

I don’t really understand why, but I’m not sure the “why” is really important. I could spend the rest of my life unpicking every single variable that led me to hole up inside myself for, like, two months.

I’ve thought about it, and I’ll think about it again: but now I’m just relieved and grateful.

Grateful for the class.

Grateful for the fact that my body is apparently rather good at putting itself back together.

Grateful especially to my friend SF (if you’re reading this, hi!), who lovingly badgered me into taking JZ’s class, and thereby has probably saved my life, or at least my career … chapeau, girlfriend.

So although I’m still … not okay, I guess, though less not okay than I was a few weeks ago, when I felt like the dark waters of my own internal whatever might finally close over my head and bear me down into their depths … I’m getting there.

I’m not saying, “I’m getting better,” because then I’ll be pissed at myself if I don’t live up to that phrase.

Everything’s back and forth, here and there, ebb and flow. I’m going to have difficult days: we’re all going to have difficult days, always, but especially now in the midst of this novel uncertainty.

But, still, I feel right now like I’ve at least managed to grab a passing bit of flotsam and I’m not fighting so hard to keep my head above water.

Some of that has come with the realization that, although the precipitous and early end of our season torpedoed the twice-weekly unofficial partnering class I was doing with a friend of mine in the company (and everything else), I have an opportunity to really work on becoming a stronger dancer right now.

Working in a less-than-ideal setting* forces me to really focus on the deepest and most essential aspects of technique–holding the core; feeling the turnout; keeping the body together. (Conveniently, JZ’s approach to teaching focuses closely on all of those things.)

*a basement with 7 foot/2.13m ceilings and very freaking hard floors

covered with foam puzzle mats** that make turning a major

challenge ^-^’

**I just put in some new portable dance flooring today. Still hard, so I’ll

be confining jumps to the puzzle mats, but better than it was.

I will be a stronger dancer next season because of the time I’m spending alone(ish) in my basement now.

That doesn’t to any extent reduce the tragedy that has arisen from some breathtakingly poor policy decisions that have led to far, far more death and suffering than was necessary in this crisis (in many countries, but especially in mine).

It doesn’t change the fact that we no longer have a clear sense of what to expect from the future (not that we ever do, but under normal circumstances, we can at least use the standard operating procedures of daily life to infer a kind of baseline normality).

It just means that maybe I, individually, am at the end of one chapter in this unexpected story and at the beginning of another (notwithstanding the utterly imaginary nature of such divisions in the first place ^-^).

I’m planning to post a list of good live video classes, and I’m working on a choreographic project specific to the current quarantine that I’m hoping to post in the next week or so.

For now, stay safe, and keep dancing ❤

Oh, and here’s a pic from last summer, just because:

This Cognitive Dissonance

If you’ve been around long enough, you’ll know that I don’t write about current events that much. I figure there are enough people out there who are better at that than I am, and thus I mostly stick to writing about ballet.

But today I’ma write about Coronavirus … again.

I’m in a weird place with this thing. On the one hand, I’m healthy AF, young, and on the surface I look a lot like someone who could easily be walking around like, “Eh, I don’t need to worry about this that much.”

On the other hand, my respiratory system—which at the moment, knock wood, is only mildly annoyed about the horror that is tree pollen—is a gigantic baby that freaks out completely at the least possible provocation.

Like, I’ve had pneumonia five times.

FIVE. Times.

I can’t even tell you how many times I’ve had bronchitis.

Ordinary ‘flu knocks me flat for 2 weeks, minimum (this is why I get flu shots, y’all … well, that and herd immunity).

And every novel respiratory illness that comes down the pike carries with it the potential for serious career setbacks or worse.

And yet.

I’m not a chronically ill person who *feels* sick most of the time. I’m a chronically ill person person who feels great most of the time, with occasional bouts of shattering illmess, some of which are terrifying.

So right now I’m walking around in the world (or, well, in my house, mostly) with part of my brain not even really thinking about this whole COVID-19 sitch, and another part occasionally going, “F**k, what if someone brings it to D’s work?”

D, btw, works in healthcare. He’s a physio, but currently works in a nursing and rehab facility, so there’s a real chance that such a thing could happen.

This doesn’t mean that I’m constantly panicking, or indeed panicking at all. Panicking won’t help. But it does mean that I’m using a lot of energy talking to my brain, trying to remind it that we have plans and stuff for things like this. That sometimes bad things happen no matter how well you plan, and that we need to stay rooted in the here and now because panicking now won’t help if something does happen.

And though it’s mostly working, my head is still in a weird place sometimes.

Anyway, life is uncertain, and the only constant is change. I’m not the best at actually practicing Zen, but I do find that even if the tools are a little rusty because you keep forgetting to actually use them, they’re still there in the garden shed when you need them, and rusty tools are better than none.

So, anyway, that helps with the cognitive dissonance a bit, as does giving myself room to feel uncomfortable.

Such is the weirdness of this mental place that it’s very hard to write about.

Also, I’m super tired, so I’m going to close here for now.

Oh: we also bought an electric jellybean—I mean, a Nissan Leaf 😊 It’s actually quite lovely and the interior is very roomy (you could fit about 5 dancers in it and still have room for a large dog behind the rear seat). I quite like it. This one’s a 2013, so the range is pretty decent. D plans to use it as his main commuter, since he works close enough to be well in range and can charge it at work. It’s a cute little car and comfortable to ride in.

It’s Complicated

So, given the fact that you’re on the internets, chances are that you’ve heard about this whole COVID-19 thing.

Resource hoarding aside (I’m looking you, single dude who lives alone and who just bought 17 cases of toilet paper), the United States actually sense to be doing a sensible, public-spirited thing and closing a lot of things down for a bit in an attempt to reduce transmission of the virus.

And I’m all for that, but at the same time it’s kind of weird and surreal.

The company’s off for the next couple of weeks, and we have no idea what’s going to happen with our last show of the season right now (Cancelled? Postponed? Performed via livestream, in HAZMAT suits?).

We did class this morning and didn’t rehearse. Starting tomorrow, we’re technically on hiatus, though we’re trying to find out if we’ll have access to the studio so we can do class together.

I genuinely had never imagined this particular outcome. It’s a weird place to be. Not bad: just weird.

I guess we’ll figure it out, going forward, a bit at a time.

Meanwhile, my teaching job is moving to an online format that’s going to be … Interesting. I’m not at all certain how I’m going to make that work, given that my house is not danceable and my data plan is utter crap. But I’ll figure something out, anyway … If we have wifi at the studio, maybe they’ll let us look in and use it for streaming.

So that’s where we are in mid-March, 2020. Things are up in the air.

My class notes today were, in short:

- Turns in 2nd: really snap that second shoulder around

- “Always finish grand allegro with a double tour, if you can” (Not sure how practicable that is, but I like the audacity of it 😁)

- Don’t create extra work for yourself

That last one pertains to a couple of things I’m working on: first, unnecessary accessory movements that require additional adjustments to balance, placement, etc; second, keeping things engaged in the right ways so the body moves as efficiently as possible.

Not rocket surgery, but worth contemplating from time to time.

Lastly, (I think) I’m done setting the choreography for “January Thaw,” so I’m planning to start polishing it next week, and I’ve started work on a new piece that I’m developing through choreographic improvisation as well.

The new piece is longer (almost 6 minutes) and a bit more complex in terms of both mechanics and artistry, and I plan to take advantage of the extra time in my schedule to really crack away at it.

I don’t have a title for it yet, but the music is Chopin again. I’ve got some rather decent video from last night, so I’ll post that sometime soon.

Partnering: It’s Ballet, Asher

For the longest time, the number one correction I got in any dance context other than ballet was, “It’s not ballet, Asher!”

Now, I’ve finally come full circle.

After rehearsal, L and I have been working on partnering stuff together, since we both want to get better at it. This has led me to realize that the sheer volume of non-traditional partnering I’ve done has been tripping me up in a ballet partnering context.

A lot of modern partnering is based in weight-sharing. You can share weight concentrically or eccentrically—in short, by pouring towards or away from your partner or partners—but either option involves a kind of nonverbal negotiation of balance.

Unless you know your partner really well and you’ve developed a strong rapport, you begin slowly.

If you’re “weighting-out,” you tentatively pour yourself away from your partner, feeling for an equal and opposite pull.

If you’re “weighting-in,” you tentatively pour yourself towards your partner, feeling for an equal and opposite push.

It’s this push-pull dynamic that gives partnering based in weight-sharing its beautiful fluid quality. As partners learn to work together, they practice conversing in a language of shared gravity—moving smoothly and silently from “weighting-out” to “weighting-in” and vice-versa.

As they learn to trust each-other and to know each-other’s weight and movement styles, the negotiation process can become so fast and smooth that it becomes invisible to the audience, but it’s always there and it’s always the same.

This is not how ballet partnering typically works.

In ballet partnering—and please note that I’m referring to the traditional, gender-specific roles for clarity, here—the girl isn’t looking for the boy to answer her weight with equal weight. She’s looking for him to be a rock-solid foundation; a kind of balletic buttress.

If you’re used to weight-sharing, you answer lightening with lightening: when your partner gives you less of her weight, you give her less of yours. Likewise, you enter into a pushing dynamic gently: it’s easy to pour too much weight into someone too fast and to knock the whole structure over.

In a ballet context, if your partner feels that you’re supporting her too lightly she tends to respond by taking her weight out of your hands to protect herself. If you’re used to weight-sharing, you’ll automatically respond by lightening and softening your contact, because that’s the typical process of negotiation.

The thing is, that’s not how ballet partnering works at all.

In ballet partnering, the girl offers her weight with the expectation that it’ll be met firmly—as if you, her partner, are a living barre.

Chances are good that if she hasn’t worked with you before, she’ll be light in your hand, so to speak: it is in her best interest not to rely too heavily on you until she’s sure that you’re up to the job.

So, basically, the least useful signal you can send in that moment is exactly the one you’re most likely to automatically send if the vast majority of your experience has been in weight-sharing.

If you respond to the lightness of her touch by offering light support, because the instincts developed through weight-sharing make you feel like you’re going to knock her over otherwise, she’ll won’t feel secure, and withdraw. If her withdrawal leads you to automatically lighten even more, she’ll also withdraw further.

It won’t take long to reach a point at which you’re not a support, but an obstacle: something she’s trying not to whack with her knee or her leg when she turns, for example, but which isn’t actually helping her turn. Needless to say, if that happens, you won’t be able to accomplish much together.

Be steady and firm, and she’ll give you more weight, so she can do the cool stuff that ballet partnering allows. She’ll also be more likely to trust you when you lift her.

Once you get past the negotiation bit, of course, things work pretty much the same way: you don’t want overpower your partner[1]. You just want to be steady and lend her just enough of your gravity and (where appropriate) your momentum or force.

- Even in lifts: you can lift another human using only your own strength, but most ballet lifts work best if you work together.

The real difference is that in weight-sharing, every movement or sequence of movements begins with and depends on a negotiation that equalizes gravity between the partners.

In ballet partnering, there is an initial negotiation, but it’s a different one. The girl silently asks, “Can I trust you to hold me up?” and the boy must answer, “Yes, I’m here,” or things aren’t going to work.

The remaining negotiation process in a ballet context is, as far as I’ve experienced, more about figuring out the physics of your specific bodies. How do you get yourself out of the way of her knee? How much liftoff does she need to help you get her into an overhead press lift? Where is her center of gravity? How does she compensate for your short li’l t-rex arms?

So, anyway, that was the breakthrough of the week for me. It’s one of those things that seems like it should be bindingly obvious—and yet I had grown so accustomed to the process of weight-sharing that I didn’t realize I was doing this unhelpful thing until this Friday.

I don’t know if any of this will be all that helpful to anyone who doesn’t share a similar set of circumstances to mine—but I hope it’ll be at least somewhat useful.

Class Notes, 03.03.2020

My penmanship is in “pretty, but not terribly legible” mode today.

“May +/ or August”

Possible masterclass dates.

“UP != BACK! CHOOSE UP!”

We did a lovely cambré, and after recovering I left my ribs a little too open and my sternum in a bit of a high release.

This does not improve one’s turns or one’s balances … Particularly not à la seconde.

Notes about back leg turnout (mostly relevant to barre and things like tendus, poses, etc—not helpful for turns, particularly):

- Recover it all the way*

- FAVOR it over front leg**

- STAY OFF THE HEEL/ON THE BALL

*I tend to be lazy about bringing my back leg fully into turnout when I close to fifth, because my specific combination of mild hyperextensions and huge calves makes it a bit more of a chore than is usual.

**By “favor it,” I really mean actually think about it. My front leg will take care of its own turnout reliably; I need to work on the back leg.

“Bring your tailbone (fouetté to arabesque).”

A lot of us were guilty of finishing a simple piqué fouetté without really bringing the pelvis with us today. I was over of them at least half the time.

“Hunger Arinn & Sefter Plié.”

This actually says, “Longer Arms & Softer Plié,” but you know. Looling for spit, etc.

“& still bring your head.”

It is always a good idea not to leave your head behind. This is especially true in ballet. That thing is heavy, yo, and since your brain’s in it you can’t just, like, take it off and leave it by your water bottle.

“Gliss no change x2, jeté pas de bourré x2, jeté assemble enrechat quatre x2.”

Mathematically speaking, I should really clarify that combination with some parentheses:

“(Gliss no change)*2, (jeté pas de bourré)*2, jeté assemble (entrechat quatre*2).”

I actually did this petit allegro right a couple of times. I mean, it’s not that complicated; it was just fast.

I’m getting better at keeping my legs under me so I don’t gallop off with myself (or over myself).

Anyway, that’s it for today’s class notes. My rehearsal notes are mostly about character development, since we’re mowing through Snow White wow effectively and I actually have time to think about that at this point.